Thomas M. Disch was born in Iowa, but both sides of his family were originally from Minnesota, and he moved back there when he was an adolescent. Although he only lived in the Twin Cities area for a few years, the state left an impression on him, and between 1984 and 1999 he veered away from the science fiction for which he had become best known to write four dark fantasy novels which have become collectively known as the “Supernatural Minnesota” sequence. The University of Minnesota Press recently republished the entire quartet, and I’ve set out to revisit each novel in turn.

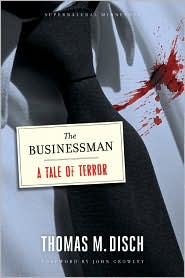

On one level, The Businessman: A Tale of Terror (1984) by Thomas M. Disch is a masterful echo of early Stephen King novels like Carrie or Cujo, tightly wound narratives that bind their horrors to narrowly bound geographies. Beyond that, though, it’s an arena in which Disch can give full license to an omnscient narrator’s voice which, as John Crowley observes in his introduction to this new edition, is richly laden with gnomic pronouncements about the world he has set in motion. In effect, he is simultaneously recreating the supernatural universe and explaining to readers how it functions, and he manages to do so without ever losing sight of the intimate story that serves as his platform.

It starts with Giselle Glandier, although we don’t know that at first: We’re introduced to her as an unnamed “suspended sphere of self-awareness” confined to her own grave, struggling to make sense of the situation. The next chapter abruptly shifts to Bob Glandier, who’s visiting a massage parlor for a lunch-hour quickie, the best method he’s found to control his violent outbursts at the office—it even comes with a recommendation from his therapist. And “he was crazy, it could not be denied. Only a crazy man would murder his wife, and that was what Glandier had done.” (After she experiences a nervous breakdown and leaves their home, he eventually tracks her to Las Vegas, strangles her, and returns home undetected.) Then there’s Joy-Ann Anker, Giselle’s mother, who’s dying of cancer at 48, with Glandier hovering over her, waiting to inherit her estate.

Their three paths soon converge; Joy-Ann goes to visit Giselle’s grave, and in dying liberates her daughter to return to the Glandier house, or, more precisely, to land in a new trap inside her husband’s brain, where she induces olfactory hallucinations until she can break out to perform more traditional forms of poltergeist activity. (This only serves to give Glandier renewed purpose: “Even though she was a ghost, she could be destroyed… and he’d do it, and it would give him unimaginable pleasure.”) Meanwhile, Joy-Ann’s afterlife begins in a hospital-like “halfway house” supervised by the real-life mid-nineteenth-century poet and actress Adah Menken. Adah alerts Joy-Ann to Giselle’s plight, and mother descends back to earth to help her daughter.

It’s around this point (a little before, actually) that Disch begins to expand the canvas by including additional perspectives. Among these, the most crucial is another historical figure: John Berryman, who committed suicide in 1972 by throwing himself off Minneapolis’s Washington Avenue Bridge. Giselle and Joy-Ann first spot Berryman as an anonymous bearded man with a head wound waving at them from below another bridge, a short distance downriver from Berryman’s jumping point. Joy-Ann dissuades Giselle from heeding his summons then, but she returns on her own a few chapters later, where he explains that he is unable to venture more than five miles from the site of his death, banished from heaven because he has refused to acknowledge Adah as his equal at verse. (“Have you ever read her poetry?” he demands. “Of course not. No one has. No one should ever have to.” Naturally, however, he has a copy in his jacket, which enables Disch to quote a brief but wretched excerpt.)

Disch’s Berryman is not an entirely sympathetic character, but he’s about as sympathetic a character as the novel will allow (with the possible exception of Joy-Ann). When Giselle becomes too despondent to act any further, Berryman takes on the task of haunting Glandier, appearing to him in the form of a lawn jockey statue and wreaking havoc throughout the house (but not before quoting some of his favorite nineteenth-century poetry). His poetic creativity is crucial to Disch’s particular casting of the supernatural realm and the way it functions; as Adah explains to Joy-Ann late in the game, “Those who possess [imagination] have an afterlife; those who does possess it, or in whom it has greatly atrophied, are reborn as plants or animals.” That imagination also includes a generous helping of the absurd: Once some of the novel’s characters are able to leave the waiting room and advance to higher stages of the afterlife, they are met at the banks of the Mississippi (or, perhaps, its spiritual/Platonic ideal) by Jesus Himself, riding in on a blimp and wearing a Salvation Army uniform.

Some readers may recognize in all this emphasis on poetry Disch’s own tough love of the form, in which he was both poet and critic both. (The Castle of Indolence is a wonderful collection of critical essays, well worth tracking down.) But what of his other major literary domain, science fiction? The novel’s one direct nod in that direction is a heavy-handed, didactic digression on the part of the omniscient narrator, who explains why.

[Glandier’s] favorite masturbatory aid was the fiction of John Norman, author of Raiders of Gor, Hunters of Gor, Marauders of Gor, Slave Girl of Gor, and, as well, of a nonfiction guide to the same shadowed realms, entitled Imaginative Sex. In that book Norman not only provided the yummy “recipes for pleasure” beloved by fans of the Gor series but he argued, as well, for the essential normalcy of man’s need to beat, rape, and abuse and, by these means, to dominate the woman he loves.

Disch would return to the theme more than a decade later, in The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of, his critical history of science fiction, adding that Norman trafficked in the same themes as “erotic” “classics” such as The Story of O, merely pitching them towards a broader audience. Here, though, it’s enough to note that science fiction fuels Glandier’s sadistic fantasies, which are eventually released in the form of a demonic “son” who possesses a dog, a heron, and an eleven-year-old boy who lives just up the street from Glandier in order to brutally slaughter anybody who could connect him to Giselle’s death. Not to worry, though: Glandier reaps a doubly just punishment in the closing chapters, and in such a way that Disch is able to circle back to one of his earliest narratorial declarations: “Hell is a tape loop that keeps playing the same stupid tune over and over and over forever and ever and ever.”

POSTSCRIPT: Because Disch himself committed suicide in 2008, it would undoubtedly be remiss not to mention that aspect of John Berryman’s life, and indeed that’s not the only time The Businessman touches upon the topic. Giselle’s decision to abandon revenge against her husband and transform herself into a willow tree might be seen as a form of suicide. More concretely, the teenage sisters of the boy possessed by Glandier’s evil impulses joke with each other about a suicide note one wrote when she was their brother’s age…and also touch upon Ordinary People, a story about the emotional aftershocks of a failed suicide attempt. The theme would become stronger as Disch’s forays into supernatural Minnesota continued.

Ron Hogan is the founding curator of Beatrice.com, one of the earliest websites dedicated to discussing books and writers. He is the author of The Stewardess Is Flying the Plane! and Getting Right with Tao, a modern rendition of the Tao Te Ching. Lately, he’s been reviewing science fiction and fantasy for Shelf Awareness.

Even in a somewhat obscure u.p. edition, I’m happy that these books are available again. They grow on me a little more every time I come back to them.

A minor point: what’s with the scare quotes around “‘erotic’ ‘classics'”? This seems to be your own editorial addition and it reads oddly here, as Disch did not use either of those words and expressed no opinion on the quality of The Story of O in The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of. I believe his point in the latter was just that kinky pulp writers got extra opprobrium because they were pulp writers, and that this is a class issue (“The Gor books are addressed to a Budweiser audience”– conflating class and cultural preferences in a way that doesn’t actually apply to Robert Glandier, who is not a working-class guy).

Also… not to make too much of this Gor thing which isn’t at all central to The Businessman, but I think it’s interesting that you saw that as a “heavy-handed, didactic digression.” I thought it was just a deadpan satirical riff that made good use of the deeply weird, icky, and fairly pathetic nature of John Norman’s oeuvre, which fits well with Glandier’s character. If you didn’t know that those were real books, you could easily assume that Disch made up Norman as an over-the-top caricature of a certain kind of genre writer, like Vonnegut did more sympathetically with Kilgore Trout. And the fact that Norman (who, like Disch, was a Midwesterner who ended up in New York) has been so prolific and successful with his creepy crap fits pretty well with the general despairing humor of the book: supernatural Minnesota is a place where there’s (almost) no justice, so of course the only science fiction fan there just reads Gor books.

Yes, the quotes around erotic and classic were both my addition, in that I did not want to appear to be using either word unequivocally. You are right that Disch frames it as a class issue in Dreams…; I was trying to use “broader” in the sense of “non-elite,” and I should have been clearer about that point.

And I can see where you’re coming from on the “deadpan satirical riff,” but my own feeling was that, even with the wider liberties the omniscient voice gave him, those particular paragraphs were reaching too far to insert a point that was supplementary background information at best. (Compare to the conversation between Father Pat in Petey in The Priest, where Philip K. Dick comes up as a much more natural follow-up to their talk of the fictional Boscage and his unusual beliefs.)

Well, it depends on how you define “too far”. I guess I see how you could read it as Disch lecturing to his readers, and/or taking an unseemly glee in holding up some really bad art for their scrutiny. But it seemed to me more like the narration dipping into Glandier’s point of view– the whole opening chapter is sort of half in his voice (Disch used this kind of limited/POV 3rd-person narration a lot, and it’s a pretty common 20th-century literary device; the omniscient parts with anonymous commentary, which is more of a 19th-century thing, are a minority). And since Glandier is nasty in sort of a petty, boring, and immature way, it makes sense that the description of his violent fantasy material is a little dry and tedious, but with the occasional jarring light note (“yummy”). I don’t think anything in these novels is actually meant as “background information”– it’s all about character and tone.

Sorry, by “opening chapter” I meant second chapter. Anyway, I’ll stop now.

That’s a fair distinction between what counts as background information and what’s necessary to set character and tone, I think.

So why the hell couldn’t they have done this a couple of years ago, when it might have done him some emotional or financial good?

Neil, maybe that was just a frustrated rhetorical question, but I can’t imagine that a university press reissue would have made more emotional difference than the imminent publication of two new novels, and a new book of poetry in the year before. As for the money, The M.D. certainly sold well before but I wouldn’t count on this edition being distributed very widely.

Things I didn’t know: The magnetic potholders that Giselle trips out on: Disch used to sell those door to door.

I didn’t know that either. Great detail! If that has a biographical connection, it makes me think that the house on fire is going to prove to be meaningful, too…

I think the benefit of the university press editions is not that they’ll fly off the shelves, but that they’ll keep books that a larger publishing house would consider “marginal” in print, much like the Wesleyan editions of Delaney’s Neveryona series. And, though I’m not sure to what extent this comes into play, maybe make them available for college literature syllabi. (I know I would teach either The M.D. or The Priest in a class on horror, or satire, or genre as social critique.)